By: Faris Mecklai

Singapore is hot. Every day had an average high of 33° and a low of 32° and the air sticks to your skin like a bug on flypaper. No one told me it would be like that. As soon as I stepped off the plane, I was blasted with a force of heat and humidity that completely caught me off guard. However, it wasn’t the heat and humidity that was the most shocking part about my arrival.

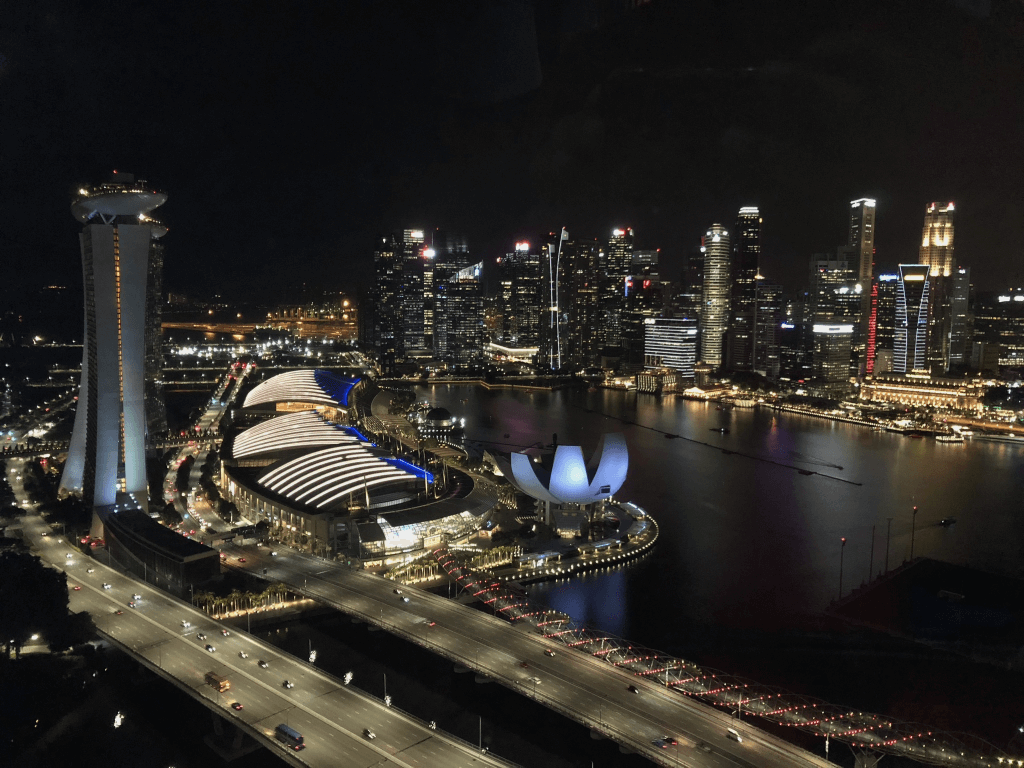

Changi Airport is basically a mall. It’s filled with luxury goods, exclusive lounges, a movie theatre, fine dining and the largest indoor waterfall in the world. My very first impression of Singapore was consumerism, and it was overwhelming. I had come to work in the non-profit sector, yet I was greeted by capitalism instead.

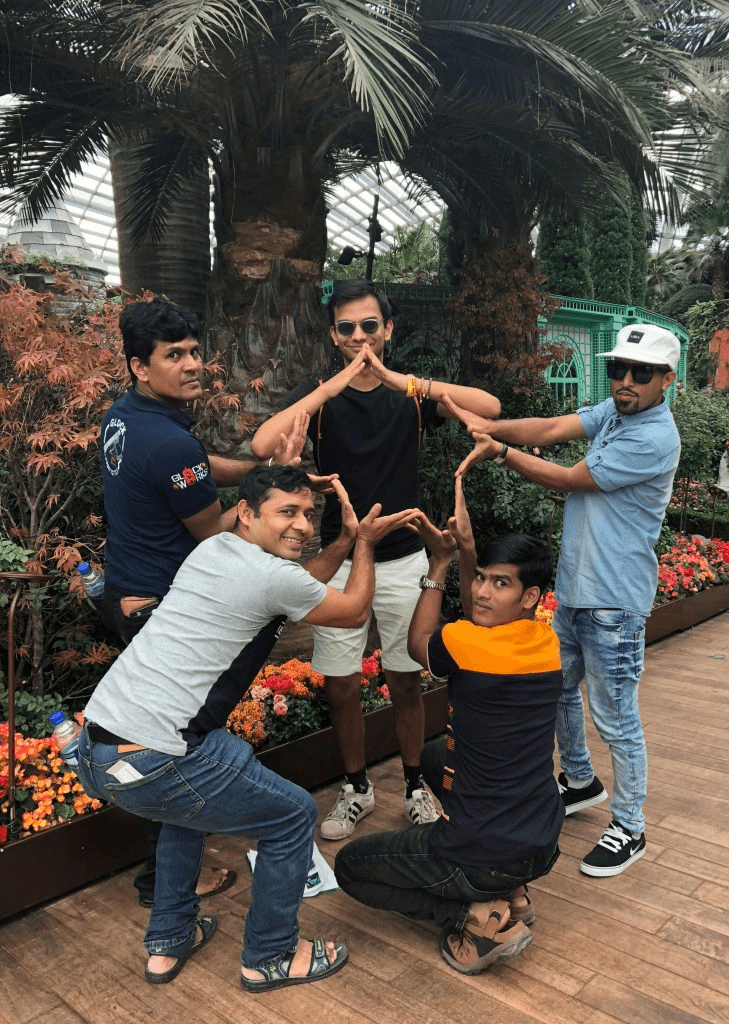

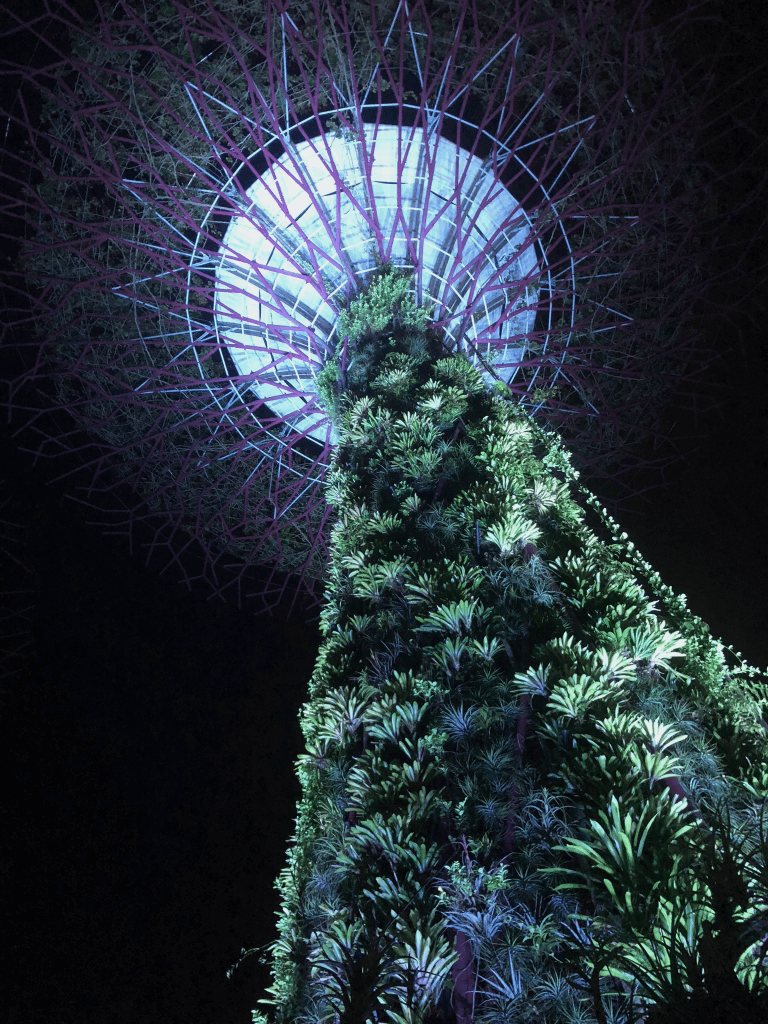

At the Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME), I worked as a casework intern helping migrant workers win salary, abuse, and exploitation claims against their employers. The bulk of my day-to-day activities involved dealing with the Ministry of Manpower (It is actually called that! I felt like I was in 1984.) or the courts. In the most efficient country in the world, I saw bureaucracy being used as a weapon to deter migrant workers from pursuing claims against their employers. I worked at the non-domestic helpdesk, which means that my clients were those who work outside of a household — typically, men from Bangladesh, China, or India who work in construction. Classified as modern-day slaves, these workers are treated as sub-humans in Singapore without sufficient pay, shelter, or rights. Nonetheless, migrant workers still flock to Singapore for the chance to earn money to send back as remittances to their families back home.

I felt incredibly guilty doing the work that I did while leading the life I led. I was supporting migrant workers fight their exploiters and an unjust system to attain a better quality of life, but I would eat at the restaurants and use the transit system they had suffered to build. I constantly saw migrant workers trying to sleep under the bright lights of the fanciest hotels that they had built because their own provided dormitories were so poorly maintained. People would walk around them without batting an eye. Singaporeans were unable to see the atrocities of their government right under their noses. It was jarring to see the disrespect for the people to whose backs Singapore’s greatness could be credited.

After a few weeks living there, once I had made local friends, I remember being at dinner talking about migrant workers’ rights and the work I was doing. I was shocked to hear the tones of apathy and ignorance in their voices.

“There’s no way they don’t make enough to survive. People in my country don’t do that.”

“The Ministry of Manpower will support them with anything.”

“It’s not my fault that they got into this mess.”

They blamed migrant workers for their own problems, rather than an unjust and racist system. They had very minimal knowledge about the people building their skyscrapers, cooking their food, and cleaning their houses. I realized that I had an obligation to educate my friends on the reality of their home and worked to instill a sense of empathy and awareness in them for the people in the background. It was at this moment that I realized that it was the Singaporean government that had ensured its citizens didn’t know that it relied on slavery to create the hyper-optimized and modern city it portrayed to the rest of the world.

When I eventually had to leave, I felt content with the work I had done for the clients I advocated for. I still have fond memories of joking with them, sharing meals in the HOME office, and hearing their stories. I also felt satisfied knowing that I had done my best to spread awareness and knowledge about the human rights abuses Singapore conducted to those I met. However, I didn’t realize that the one person I forgot to educate was myself. We in Canada are no different than the Singaporeans who had no idea what was going on right in front of them. The only difference is, instead of building skyscrapers, the migrant workers in Canada are working on farms. Perhaps it’s because they are living much further out of cities, but I realized that my knowledge about temporary migrant workers in Canada was extremely limited.

So, I started to educate myself. Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that, just like Singapore, we abuse, exploit, and capitalize on the very hands that give us allow us to live without thinking twice about their well-being. Now, I talk about Singapore and Canada when I meet people who may not understand their privilege, and I don’t plan on stopping anytime soon.

About “We Are Not So Different You & I”

“We Are Not So Different You & I” was written as part of the Write and Tell Your Story workshop series during International Education Week (IEW). This story also won second place in the IEW Writing Contest.

Faris is an Arts and Science student in the middle of his third year at McMaster.

Stories for a global community

Throughout IEW, students shared how recent experiences enhanced their global perspective and contributed to their intercultural skills. Experiences included:

- Remote or virtual experiences

- Experiences abroad (studying, working, volunteering, researching, etc.)

- International student experiences

- Out-of-province experiences

- Participation through clubs and organizations with an international or global perspective